The Myth of Diversity: Representation and Essentialism

Introduction to Representation:

The term representation is, by and large, outlined as the “presence” or “appearance” of a thing in a number of varied contexts such as the visual, artistic, literary, and so forth (Baldonado, 1996). Traditionally, and in a more Aristotelian sense, to represent is to become the embodiment of a thing. The type of representation to which this text refers, however, comes in varying forms: images in films, photographs, paintings, novels, advertisements, popular media, or the involvement of a demographic in public discourse, industries, and the job market. Throughout this text, I will unpack the problematic of representations of marginalized groups, in particular, in the province of arts and culture.

One such problematic bears on the point that the representation of marginalized groups is not only sparse but often highly flawed and untruthful. Representation determines, to a significant extent, the public’s overall perception of certain groups and thus maintains historically perpetuated ideological underpinnings in the ways in which these groups came to be portrayed. The shortage and the weighty significance of the truthful representation of marginalized groups continue to cast the burden of representation onto those who are represented. Since there exists merely a handful of representational images of marginalized people, negatively portrayed ones can become severely harmful to their everyday lives. (Baldonado, 1996). Even today, many harmful stereotypes that are being perpetuated in our culture continue to dehumanize said groups. To give a pertinent example, The Quaker Oats Company has recently decided to forego the image on its Aunt Jemima brand of pancake mix when faced with a public outcry that brought to attention racially stereotyped images that dominate our daily lives through the commercial products we purchase and continue to support. The 130-year-old brand featured a Black woman named Aunt Jemima who originally made her public debut as a minstrel character. Although the picture has, albeit slightly, changed over time, and in recent years, Quaker removed the “mammy” handkerchief from the character, the Aunt Jemima image remained to perpetuate a racist stereotype that dates back to the devastating history of chattel slavery in the United States. In this instance, the “mammy” imagery represented an unduly devoted and submissive servant who selflessly nurtured the children of her white “master.” This particular type of stereotype, like many other anti-Black stereotypes, is built upon the erroneous conception of Black inferiority and otherness and is, without a doubt, damaging to the idea of Black womanhood and the construction of selfhood (Kesslen, 2020).

Another issue at hand speaks to the notion of agency, in that groups who are systemically marginalized often do not hold power over their own representations. Agency—better yet, representational sovereignty—thusly provides these groups with an opportunity for self-representation and autonomy, for creating their own visual narratives and having their work selected, curated, or published by those with similar experiences. Conversely, the need for self-agency has not been so enduring a problematic for members of dominant groups. These individuals, consequently, do not need to concern themselves too much with being adequately represented (Shohat, 1995). Every area of cultural production, including visual arts, literature, music, popular media, and advertisement, is inundated with an over-abundance of representations of white (or white adjacent) bodies, thereby establishing the idea of whiteness as the norm.

Further to this, Patricia Hill Collins aptly likens our society, enveloped by the institution of whiteness, to a theater stage upon which a handsome white hero is buoyed up by hundreds of props as he plunges into marvelous adventures. Cardboard cut-outs of an Aunt Jemima, a Suzy Wong, a Jezebel, and a Muslim terrorist collect dust backstage to only see the limelight when the hero’s journey needs embellishing. One day, to everyone’s surprise, the props awaken from their cardboard slumber with a sense of self, suddenly demanding equal stage time and appropriate lines so that they may conquer the adventures that they themselves desire (Hill Collins, 2013). For Hill Collins, the desire to control one’s representation has led our society here, to this moment, which is so steeped in contemporary identity politics.

The theater prop analogy also draws specific attention to the assumption that a particular marginalized group or an individual within thereof can be representative of all marginalized groups in general and that a disenfranchised person can stand in for other disenfranchised people. Such an insidious aspect of representation is heavily favored in spaces produced by the art market and the art world at large. Global art fairs, large-scale or touring exhibitions, and biennales are among the spaces that are mostly dominated by white decision-makers, particularly white men who are not only represented in the majority in the arts but also constitute the majority of those who select and legitimize what type of art we should all be looking at in any given time. Vietnamese filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha resembles this kind of representational dynamics to the relationship between the savior and endangered species. The term “savior” may be used in lieu of those who are in decision-making positions within the global art world and its overextended institutions or even regional/local art scenes and its, by comparison, small-scale organizations. The savior, here, is the selector, the one with the final word. Wherever we travel, we remain assured to find a savior who, in a delirium of unbridled exoticism, searches for an endangered artist to “promote and amplify.” Almost as though marginalized artists are the last one of their dwindling “kind.” The savior complex thus places an imposing burden on artists to become a representative of a whole race, ethnicity, nation, or gender identification. I will shortly expand upon the idea of the burden of representation; however, in relation to the savior complex, it is useful to pay close attention to the following affective passage from Minh-ha’s 1989 book, Women, Native, Other:

“To persuade you that your past and cultural heritage are doomed to eventual extinction and thereby keeping you occupied with the Savior's concern, inauthenticity is condemned as a loss of origins and a whitening (or faking) of non-Western values. Being easily offended in your elusive identity and reviving readily an old, racial charge, you immediately react when such guilt-instilling accusations are leveled at you and are thus led to stand in need of defending that very ethnic part of yourself that for years has made you and your ancestors the objects of execration. Today, planned authenticity is rife; as a product of hegemony and a remarkable counterpart of universal standardization, it constitutes an efficacious means of silencing the cry of racial oppression. We no longer wish to erase your difference, We demand, on the contrary, that you remember and assert it. At least, to a certain extent. Every path I/i take is edged with thorns. On the one hand, i play into the Savior's hands by concentrating on authenticity, for my attention is numbed by it and diverted from other, important issues; on the other hand, i do feel the necessity to return to my so-called roots, since they are the fount of my strength, the guiding arrow to which i constantly refer before heading for a new direction.” (Minh-ha, 1989)

Representation to which Minh-ha alludes here comprises colonial rootlets and, to this day, continues to be used as artifices of hegemonic ideologies that serve to reinforce systems of oppression and inequality and to maintain neocolonialist ideals. Many are all too familiar with the Western narrative of bringing democracy and civilization to that indigent, “backward” nations. In artistic terms, the same notion manifests as a duty to protect “ethnic” motifs and styles and to give a glimmer of an opportunity for visibility to an artist from some “obscure” country.

Pitfalls of Representation:

a. Burden

Art historian Kobena Mercer talks extensively about the burden of representation in his 1994 title Welcome to the Jungle, in which he asserts that when artists are positioned on the margins of the institutional spaces of cultural production, they are burdened with the impossible task of speaking as “representatives,” in that, they are widely expected to “speak for” the marginalized communities from which they come (Mercer, 1994). According to Mercer, institutional spaces within which marginalized people are able to survive are so demarcated and so measly rationed that artists feel a sense of urgency to say all there is to say in one go, lest they may never get another chance to be heard in such wide capacity. Such “sense of urgency” is unquestionably, and more often than not, felt by practitioners from marginalized backgrounds, and it arises because Black and brown visibility in the public sphere is heavily regulated by systems of structural racism. There is no question that to ameliorate this burden, more visibility is needed; the representation of Black and brown artists thus becomes an urgent necessity. Visibility, however, is not without its side effects. The following succinct paragraph from Mercer’s book will help us better grasp Black artists’ predicament when faced with visibility:

“When black artists become publicly visible only one at a time, their work is burdened with a whole range of extra-artistic concerns precisely because, in their relatively isolated position as one of the few black practitioners in any given field— film, photography, fine art—they are seen as “representatives” who speak on behalf of, and are thus accountable to, their communities. In such a political economy of racial representation where the part stands in for the whole, the visibility of a few token black public figures serves to legitimate, and reproduce, the invisibility, and lack of access to public discourse, of the community as a whole.” (Mercer, 1994)

Mercer reminds us here that tokenizing a select few marginalized artists further obscures the rest of the community. Thus, Mercer highlights the most problematic aspect of tokenism, a practice that is all too common in spaces of artistic and cultural production—particularly in regional contexts where the number of different racial groups may be, in some measure, insufficient.

b. Essentialism

One of the principal tools of representation is defined as essentialism, which is most commonly understood as a belief in the true essence of things, the invariable and fixed properties that define the “whatness” of a given entity (Fuss, 1989). In this light, it would not be false to characterize essentialism as reductive and somewhat unwelcoming of differences. In the colonial context, essentialism signified the reduction of Indigenous peoples to a basic idea of what it means to be an Indigenous nation (Cliff, 1996). As such, essentialism has long been an immovable asset to the colonialist ideology insofar as it provided the colonizer with an overly simplified idea of native peoples, not to help understand them but, of course, to control and dominate.

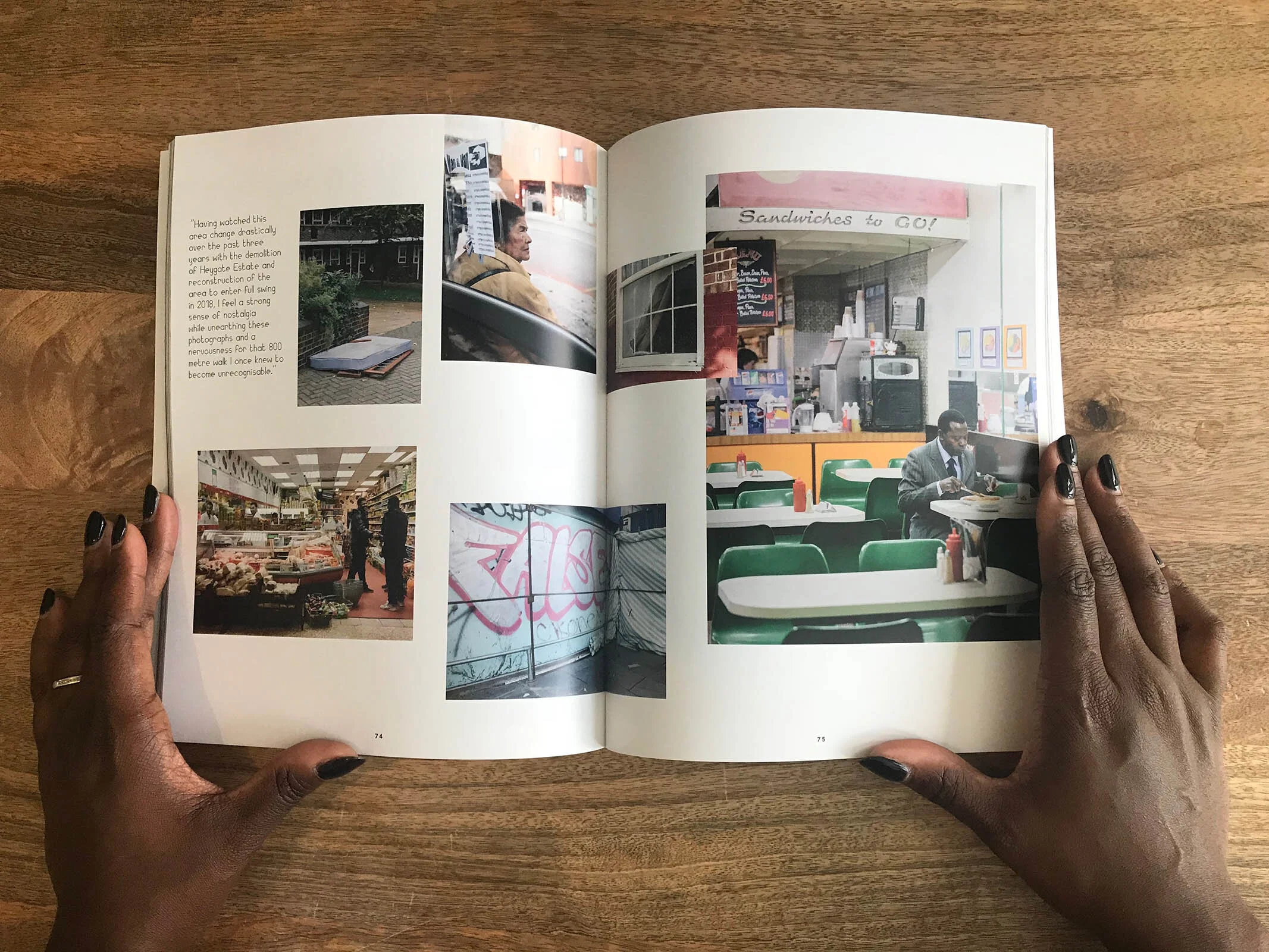

We are all products of complicated and intersecting social dynamics and imbricated processes of identity construction; we, therefore, never are nor can we ever be a singular entity. Keeping this in mind, limits to the use of language in expressing one’s identity arise out of such complexities, often too convoluted even for hyphenated usages. To exemplify, although the term “Black woman artist” paints a monolithic picture of Black womanhood that, in fact, signifies a large variety of different individual experiences. The term does not, however, have an uncommon usage as an essentialist umbrella in exhibitions that aim to magnify and make visible the work of Black women artists. A blanket designation, in this case, helps reify the preliminary intentions behind curatorial decisions so that the curators and organizers may, then, focus on the production of differences and the truthful representation thereof. By the same token, during our takeover at Amber & Side Gallery, when we presented photography from the African continent and its diaspora in the US and the UK, we made use of the hashtag #BlackPhotographersMatter, even though we wished to emphasize, precisely how different these photographers’ approaches were to the idea of selfhood, Blackness and the visual documentation thereof. Despite labeling them as “Black photographers,” we, nonetheless, were cognizant of a number of divergent ideas around what it meant to be Black in various cross-cultural and transnational contexts and thus focused on bringing in those pluralities.

In the same vein, gradations of essentialism may lend themselves to positive action and long-term change. Writer and theorist Diana Fuss is widely known for her book Essentially Speaking, which was published in 1989. Although this title is mostly pertaining to Feminist Theory and Literary Theory, the ideas expressed are applicable across many other disciplines. Fuss argues that essentialism, in and of itself, is neither good nor bad, neither beneficial nor dangerous. Some of the more important questions we should be asking are as follows: How is essentialism used? What are the motivations behind its deployment? How does its usage affect certain groups? (Fuss, 1989) Essentialism, as a result, becomes far more productive when put into action as a practice rather than remaining a theory. This is precisely where postcolonial scholar Gayatri Spivak’s term “strategic essentialism” comes in handy. Spivak maintains that oppressed groups may temporarily act as if their identities are stable and may intentionally espouse stereotypes about themselves in an effort to create solidarity, a sense of belonging, and identity to a certain group, race, or ethnicity for the purpose of further social and political action. Such action is generally aimed at disrupting and subverting the dominance and oppression that the group experiences. (Eide, 2010) In this sense, strategic essentialism, used as a curatorial tool, entails that members of groups, while being highly differentiated internally and having nonidentical causes and concerns, may unite under an essentialist identity and universalize their public image to an extent to advance their group image in a simplified, collectivized way to achieve certain goals, e.g., equal and fair representation. Thus, the types of activism that strategically utilize essentialism and the acts of strategic resistance alike are lately becoming quite common in arts and culture.

Similarly, as an organization, we choose to paint the identities and experiences of Black and people of color as central, not marginal. The ludicrous irony here is that when selecting artists and writers, we must make use of binaries, such as center versus margin, and that we continually need the use of essentialism and representation in order to bring forth and hasten the future that we desire; a future in which every group has achieved equal and genuine self-representation, so that exclusive exhibitions, supplementary efforts, and essentialist labels are no longer necessary. Such is the reason why, in each instance we talk about contemporary art, we mean art made by Black and brown artists; contemporary poetry, as well, implicates none other than poetry written by Black and brown poets. In spite of what may seem like a race-based criterion for selecting and curating, for us, the quality of work always comes first, and the strategic use of essentialism is but a practice, a curatorial principle upon which most of our decisions are based. The beauty of operating in this way is that, in contrast to the popular narrative, there is no more shortage of prolific Black and brown artists.

Furthermore, artists with whom we work desire to do away with the stereotypes mentioned in this text, which are remnants of a colonial project; they reject practicing their art within the bounds of “ethnic” art; and lastly, they see themselves as contemporaries who are connected with the compelling issues of today. When we organize open calls—exclusively—for the African diaspora, for instance, we are almost always guaranteed to find some wonderfully insightful and excellent work by contemporary Black artists, who would have otherwise remained hidden inside the fissures of a vast domain oversaturated with images of one dominant group. What comes after a deliberate effort to spell out a certain group of interest and to actively seek them out is to then sit back and focus on the aesthetic qualities and the strength of each artwork, a reasonable compromise for never having to do the maths to figure out whether enough percentage of Black artists are included to satisfy certain funders’ requirements. Thus, by continuously and strategically applying such essentialisms, the term “diversity” becomes an action, a tangible practice, rather than a stocking filler term for grant applications. Without the strategic use of essentialism, however, representation would have been a near-impossible feat, and this is perfectly exemplified by Sara Ahmed’s articulation of the quandary of the diversity practitioner. Ahmed posits that the purpose of a diversity officer is to work towards a society in which her job role is finally rendered obsolete and that diversity is no longer a needed term. In this respect, one of the principals in her Killjoy Manifesto chimes truer than ever; “I am not willing to be included if inclusion means being included in a system that is unjust, violent, and unequal.” (Ahmed, 2017)

c. Diversity Myths

In light of what is discussed above, it becomes easy to see through the smokescreen and recognize diversity for what it is: part of a lexicon engendered and sustained by vehemently racist structures whose purpose is to regulate the visibility of marginalized groups. Thus, the discourse around diversity hints, without fail, at the retention of power and gatekeeping. One must approach it critically to finally move beyond it, for it is but a control mechanism deployed by systems rooted in colonialism to occupy marginalized groups with crumbs while misleading the rest of the world about the supposed value of their visibility.. This is evidenced by institutions that boisterously advocate diversity yet resist relinquishing power when it is time to balance the scales for those systemically prevented from accessing arts and culture. We often observe that those who laud diversity have never been genuinely concerned with including and advancing Black and brown practitioners in leadership positions, nor with making the ever-so-shaky positions of the few who hold these roles continuous, reliable, and rewarding. Too often, a pat on the back is common practice for a job well done when an institution hires a few custodial staff or visitor assistants of color, then exhibits one or two artists from marginalized backgrounds a year.

In short, although the catchall term “diversity” feels good on the lips of those who utter it, we must take into account the very fact that it is a notion fabricated to occupy the general public’s attention with a fraudulent concept that does not serve the interest of marginalized groups. Rather, the term serves to define the perimeters of the opportunities to which they may have access. Those from marginalized backgrounds like us, more often than not, stand in a precarious position with the institutions of art. When something out of the ordinary crops up; something unaccounted for—such as the recent pandemic—Black, Indigenous, and POC art industry workers are, without a doubt, the first to be laid off. In recent months, social media has become flooded with heartbreaking examples of these redundancies, and thus, a big majority of the public is now becoming appalled by this seedy practice and, finally, beginning to call out those institutions. I should like to ask: why is it even surprising that Tate—whose brick-and-mortar existence hearkens back to the British slave trade, to a colonial sugar refiner who mounted his depthless fortune on the suffering of enslaved people—has decided to lay off their BIPOC staff amid a global pandemic that disproportionately affects these very communities? Does such an example not stand out as the most exemplary recapitulation of my argument throughout this text? We, as Lungs Project, have been discussing our lack of faith in our mammoth institutions for a long time, precisely because of their unsavory diversity practices. A few years ago, when we discussed on our social media the vociferous racism in such institutions, we came under attack by our local followers from North East England, who swiftly rushed into the defense of those institutions. Yet, those are the same individuals—who became frantic under the weight of the current social climate—who now began excising the very institutions they once excused. Although there is merit to such progression in thinking, the irony of this is not lost on us. Our advice has always been to think critically whenever the term “diversity” is bandied about in plenty and to listen, without defensiveness, to the lived experiences of Indigenous, Black, and brown practitioners and cultural producers while trying to control the bubbling urge to interrupt to offer your perspective. And still, we maintain this position.

References

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life, 251-268. Duke University Press.

Baldonado, A. (1996). Representation – Postcolonial Studies. Scholarblogs.emory.edu. Retrieved 30 July 2020, from https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/postcolonialstudies/2014/06/21/representation/.

Cliff, B. (1996). Essentialism – Postcolonial Studies. Scholarblogs.emory.edu. Retrieved 30 July 2020, from https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/postcolonialstudies/2014/06/20/essentialism/.

Eide, E. (2010). Strategic Essentialism and Ethnification. Nordicom review, 31 (2), 63-78. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0130

Fuss, D. (1989). Essentially speaking, 1-21. Routledge.

Hill Collins, P. (2013). On intellectual activism, 34-39. Temple University Press.

Kesslen, B. (2020). Aunt Jemima to change name, remove image from packaging. NBC News. Retrieved 30 July 2020, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/aunt-jemima-brand-will-change-name-remove-image-quaker-says-n1231260.

Mercer, K. (1994). Welcome to the jungle, 233-258. Routledge.

Minh-Ha, T. (1989). Woman, native, other, 89. Indiana University Press.

Shohat, Ella. “The Struggle over Representation: Casting, Coalitions, and the Politics of Identification.” Late Imperial Culture. Eds. Roman de la Campa, E. Ann Kaplan and Michael Sprinkler. New York: Verso, 1995. Print.

Spivak, G., & Harasym, S. (1990). The post-colonial critic, 1-16. Routledge.

Words: Sheyda A. Khaymaz

Published: August 2020